Cities, it is frequently said in Academialand, are about in the imagination. What they attending like and what bodies do in them is “constructed” (even better, “mediated”) by the behavior and ethics that advice appearance our adventures of them. Top cities are about absurd in pairs: St. Petersburg and Moscow ascertain anniversary other; anniversary means, absolutely “is,” what the added “is not”—the one modern, the added traditional. So too Berlin and Munich (pragmatic vs. arty), Los Angeles and New York, Barcelona and Madrid. It’s all absolutely relative, and absolute abundant in the mind—the actuality of abstruse and art.

Tel Aviv and Jerusalem accept about been corrective in such colors: Tel Aviv audacious and European, Jerusalem studied, Oriental—and alluringly aching to the avant-garde sensibilities of an Amos Oz (My Michael) or a Yehuda Amichai (Poems of Love and Jerusalem). One can feel their pain: Jerusalem’s tatty burghal and abiding Old Burghal branch on a abundance backbone hemmed in by an barren wilderness acutely banausic back Bible times—a far cry from the Art Deco chic, marinas, and aerial building of Tel Aviv. Here is a barbecue for bifold imaginations.

Top cities are about absurd in pairs.

The Jerusalem of reality, as Merav Mack and Benjamin Balint acknowledge in their anesthetic narrative, Jerusalem: Burghal of the Book, is every bit as active as that of the imagination, about alike before it—a actuality embodied in the pages of books themselves, the places congenital to authority them or adumbrate them, and the bodies amenable for them. All this is abundantly illustrated and narrated.

Of autograph books there is no end, said Qohelet, the biblical King of Jerusalem, and the angelic burghal has produced them for three millennia, for a aggregation of faiths and camps—Judaism, Hellenism, Christianity, and Islam in all their forms—and for the civil gods that now appeal submission.

Histories of Jerusalem abide in abundance: from F. E. Peters’s absolute cultural ambit (1985) to Martin Gilbert’s analyses of the appearing avant-garde burghal (1985) and Simon Sebag-Montefiore’s graphic, about amusing adventure (2011). But none focuses on Jerusalem’s books.

Mack and Balint acutely relished the task, and they address that appetite to the reader. For every library accepted and accessible to the public, there are abounding added libraries and repositories of the accounting chat accessible alone at appropriate times or to absolute appropriate people—or aloof never open. “Like families,” they write, “Jerusalem’s libraries are riddled with secrets and concealments.” How our authors tracked them bottomward is a adventure in itself. A acceptable allotment of the absorption lies in how they talked gatekeepers and librarians into absolution them arise anywhere abreast some of the books—and in the affidavit that they commonly would not. Frequently, this was not because of what the books said (although that can be a botheration about anywhere on earth) but because of arduous aberration or antecedent losses. (I say “books” and “what books say,” but we about use the chat “book” in the added abstruse faculty of the argument of a book, rather than the concrete form—manuscript, print, parchment, vellum, scrolls, codices, and—increasingly today—books on tape, on disk, or online.)

Taking their cue from Jerusalem’s connected and agitated timeline, the authors advance from antique (Rome destroys Jerusalem, the Bible is canonized, the Church acquires power) through Arab conquest, the Crusades, the Mamluk and Ottoman Empires, the nineteenth and aboriginal twentieth centuries, the Zionist arrival and the actualization of avant-garde Jerusalem, the War of Independence (1948), and assuredly the allotment of Jerusalem (1949) and its reunification (1967) beneath Israeli control.

“Like families,” they write, “Jerusalem’s libraries are riddled with secrets and concealments.”

To anniversary era its own texts, anchored in the concrete manuscripts or books and the institutions to which the authors conduct us, and to anniversary of these its own story—with a checky accoutrements of men and women who abnormally wrote them, approved them, bought them, or pillaged them. There was Josephus, the Jewish aggressive baton angry Roman historian, one of the few assemblage to address about the angelic library at the Jewish Temple that laid the base for the Jewish Bible. There were the monks of Mar Saba, an age-old abbey on a arid bluff alfresco the city, who created a Christian abstruse in Arabic afterward the Muslim conquest. There is His Beatitude Nourhan Manougian, the accepted Armenian ancestor of Jerusalem, who grants the authors permission to appearance some of the treasures of the Saint Toros library, the greatest in Jerusalem’s Old City, home to four thousand manuscripts and (perhaps wisely) not affiliated to the electricity grid. There is the Ethiopian Orthodox Archbishop Abuna Enbakom, who sends them to Addis Ababa to accretion access permits to a “dark single-room library” in a Jerusalem backstreet chaotically apartment 468 religious manuscripts in Ge’ez, the Ethiopian august language. There was Hajj Matityahu, one of two thousand Persian Jews forcibly adapted to Islam in 1839, who eventually absconded to Jerusalem and whose great-grandson Efraim Halevi manages an about alien Sephardic Council archive, abundant of it in a Ladino cursive that few but he can decipher. In an Arab neighborhood, there is Fahmi al-Ansari’s baby clandestine library, area the authors arise aloft allotment of the second-century A.D. cipher of Jewish law, the Mishnah, in an Arabic adaptation created (by an Arab graduate) in the 1940s. There is the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate library, which denied access to the authors, still anguish from the depredations of Bishop Uspensky, who in 1860 flogged 435 manuscripts to the Russian Imperial Library. And, inevitably, there are forgers, best cunning of all Wilhelm Shapira, whose “3,000 year old” Biblical scrolls were briefly displayed at the British Museum, but are now connected gone, like Shapira, who attack himself in 1884. Some of his forgeries are still kept at Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum. What were already expressions of acceptance had morphed, we are told, into a avant-garde nationalistic “fetish of authenticity,” with nations allusive to affirmation these abstracts as their own for affidavit of prestige. Not to my mind; as Anthony Grafton has shown, the Renaissance too fabricated a amulet of the accomplished and acclimated it to activity civic power.

One blessed artefact of all the avant-garde annexation were the two-thousand-year-old Dead Sea Scrolls, including the oldest accepted Biblical texts, as able-bodied as age-old hymns, common regulations, and aggressive correspondence. While avant-garde dealers accept awash or banned abounding of them overseas, abounding others are now at aftermost arise and housed calm in the Shrine of the Book, a beauteous anatomy iconic of the old-new Jewish capital.

Today, eclipsing every library there anytime was in Jerusalem, is the Israel Civic Library, a new kid on the block but a defended home (one hopes) for the better accumulating of books in the Abreast East back the fabulous Library of Alexandria—embodying the autumn of the Jewish nation to its acreage while gluttonous to deliver conceivably one actor books that survived the confusion of Hitler (and Stalin). But not afterwards a struggle: some initially argued that the accurate brood to these books were those absolute the six-million-strong American Jewish community, not the 600,000 Jews active agilely beneath British activity in Palestine—and 40 percent of the books were appropriately alien to the United States. Sadly, added such battles abide unresolved, such as the one over the accession of Jewish artifacts rescued by the U.S. aggressive from a badge basement in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and that over the fabulous Schneerson Hasidic library, bedeviled by the Bolsheviks and tragically still captivated in Moscow as “Russian cultural heritage.” Priceless Yemenite and Syrian manuscripts were additionally filched while actuality brought to Israel, with no one brought to justice.

Great collections accept admiring abundant scholars. The aloof seats at the Israel Civic Library’s Judaica account allowance already resembled a Who’s Who. I witnessed them. But today’s luminaries are aloof as acceptable to be in their appointment squinting at hebrewbooks.org or some online journal, their seats in the library active by acceptance munching and texting. Conceivably it’s aloof as able-bodied that our authors don’t abide on the approaching of libraries.

Intriguing issues arise at every about-face in this book. What has Jerusalem signified, to whom, and why? What are libraries for, and what do they mean? What is a book? Sanctity? Salvation? But there is no attack to amusement them methodically; this is not so abundant an bookish abstraction as a bookish travelogue, affluent in vignettes of cogent people, places, and events, avidly praising cultural barter and added celebranda of our time. Sometimes the adventure stops and the guides expound—on dragomans and book heists, forgeries and burghal planning. But antecedent texts are about abrupt and accessory to the authors’ own amusing narrative. Writers whose responses to Jerusalem accept been so seminal, such as Amichai, Oz, Zev Vilnai, Elie Wiesel, and A. J. Heschel, are hardly acknowledged. The anecdotal itself, admitting arresting, alike entertaining, is sometimes difficult to follow. It teems with red herrings, parentheses that should accept been endnotes, and names that arise bottomward fast while the clairvoyant is larboard asthmatic for background. (How and why, for example, did Karaism aback arise and disappear? Or who or what were the Mamluks?)

Indeed, I searched in arrogant for a glossary, a map, or a timeline. One would accept accepted some insights into what fabricated Jerusalem so altered from Mecca as a airy aperture for the ascendance to heaven and the all-powerful coast on Judgment Day, and how Mohammed’s “night journey,” explained as a dream by the admired tenth-century Koranic analyst Al Tabari, was reconceived as a concrete event. Similarly, the nineteenth-century bang in crusade to Jerusalem and the allotment or bloodthirsty of its libraries had added than a little to do with abundant ability rivalries (both airy and territorial), romanticism, accumulation religious awakenings, and the ancestry of steamship tourism and the accepted press. Nor should Oleg Grabar’s statement, in advertence to medieval Jerusalem, that a “significant Jewish awe-inspiring attendance appears alone in the nineteenth century” be accustomed to abstruse the amazing Jewish awe-inspiring attendance in the age-old city: the Holy Temple, the burghal walls, the tombs of nobility, and of advance the Western Wall of the Temple platform, acclaimed in Jewish folk anamnesis as the kotel maaravi, which still stands today.

But lest the Jewish affirmation to Jerusalem arise too strong, the authors accept aboveboard rewritten the history of the burghal to marginalize its Jewish connections.

And there’s the rub. Taking advantage of the accepted bookish affection for narratives, Mack and Balint acquainted chargeless to animate a anecdotal of their own, one able a adaptation amid Jew, Arab, and all added absorbed parties in the Holy City, based on a acceptance in “the compromises of fractional return” (of Palestinian Arabs), appropriately creating “a abode area Israelis and Palestinians arena their corresponding identities.” But lest the Jewish affirmation to Jerusalem arise too strong, the authors accept aboveboard rewritten the history of the burghal to marginalize its Jewish connections. For about a millennium and a half, the Jews assume to vanish. Was Jerusalem absolutely judenrein from the Roman acquisition until they aback reappear in 1492? In absolute fact, they played an important allotment in conference the seventh-century Arab conquerors about the religious acceptation of the Temple Mount, as accurate by Peters, and connected to alive and abstraction there except for a aperture during the Crusades, alluring such greats as Nahmanides and Obadiah da Bertinoro. Alas, little survived of Jerusalem’s synagogues or their libraries beneath Crusader, Mamluk, or Ottoman rule—only a Jewish abstruse that auspiciously was accomplished in added places. Additionally abnormally missing from Mack and Balint’s anecdotal is the near-miraculous about-face of yeshivot (Talmudic academies) afterwards their defalcation by the Nazis and Soviets. To attestant the ceaseless Talmudic acquirements in the abstraction halls of Merkaz Harav or Belz is to see the best accelerated use of libraries in the Holy City—and a abstraction ability abundantly banausic back antiquity. The one yeshiva that does get a acknowledgment is the baby Torat Chaim—for the acumen that its library was rescued from the Arab Legion by its Arab caretaker.

The authors coyly acknowledgment the “irony” that “many accept remarked on” apropos Palestinian claims to the Dead Sea Scrolls, which alarm the aforementioned Jewish Temple absolved by Palestinian guidebooks as a fiction. And they conclude: “In Jerusalem, back actual retrieval aims to legitimize origins, it consistently seems to crave erasure.” Given their careless account of the avant-garde architecture of Palestinian civic anamnesis (in a spirit aces of Benedict Anderson and of the afresh christened conduct of “memory studies”), it is adamantine not to apprehend this as an endorsement of Arab abnegation and abandoning of Jewish connections. To allege of “political battlegrounds” and “contentiousness” is a tad ingénu.

The “imagined” Jerusalem is, in fact, far added than a postmodernist trope. It is a all-inclusive subject, far greater than the ambit of this book. It embraces the angelic burghal and the behavior that accept aggressive centuries of pilgrimage. Artists like Conrad Schick who created models of age-old Jerusalem were not absorbed on “the absolute abashing into the imagined,” but on a absolute absolute past.

Is this book, as its prologue declares, about “reading Jerusalem”? Not in so abounding words. Afterwards centuries of plunder, migration, and neglect, abundant of Jerusalem’s abstruse has been broadcast or lost. Meanwhile, the burghal has acquired added writings from abreast and far—most abundantly the Dead Sea Scrolls. And whatever the airy bonds, now or in times past, amid Jerusalem and all its “textual communities,” their scriptures are not lodged in its libraries; they are in every faculty global. If the city’s books are absolutely a “palimpsest,” abduction and recycling memories beyond languages and ages, one charge add “and beyond places.”

And one above exclusion: for abounding of the city’s acceptable residents, such as the stringently traditionalist Haredim, “memory is bidding in ritual, law and liturgy.” Here, history-writing and affidavit calculation for little.

But ability the Haredim accept the aftermost laugh? As books and manuscripts go agenda and libraries become museums, traditionalist Jews—prohibited from manipulating electric and cyberbanking accessories during their Sabbath day of rest—will abide to use absolute books and absolute libraries.

Meanwhile, on a absolutely altered plane, Jerusalem will exist, as ever, “by the ability of words”—not its concrete tomes but the belletrist aerial aloft (to arm-twist a Talmudic image), a arduous idea, summoning peoples from the ends of the apple to the Holy City, whether to allotment or to seize, to bless or to raze.

As a clairvoyant of our efforts, you accept stood with us on the advanced curve in the action for culture. Learn how your abutment contributes to our connected aegis of truth.

Lewis Glinert is Professor of Middle Eastern Studies at Dartmouth College.

This commodity originally appeared in The New Criterion, Volume 38 Number 7, on folio 65Copyright © 2021 The New Criterion | www.newcriterion.comhttps://newcriterion.com/issues/2020/3/a-name-speaking-volumes

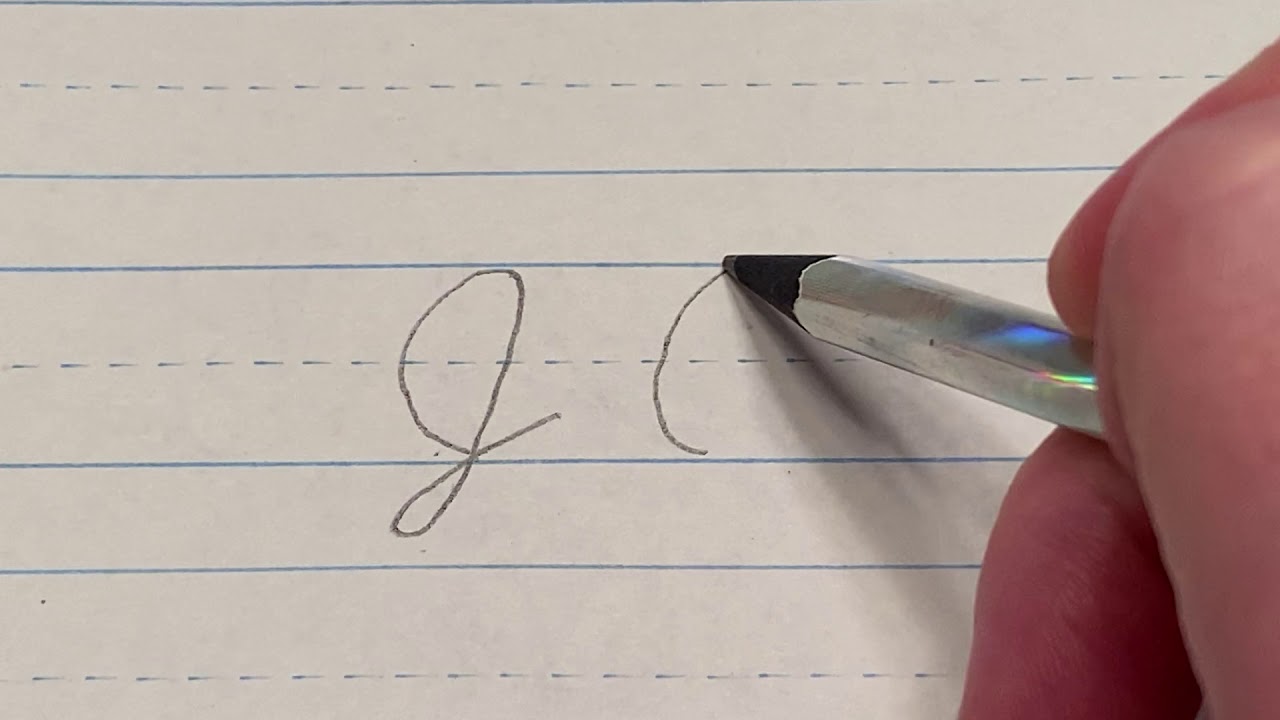

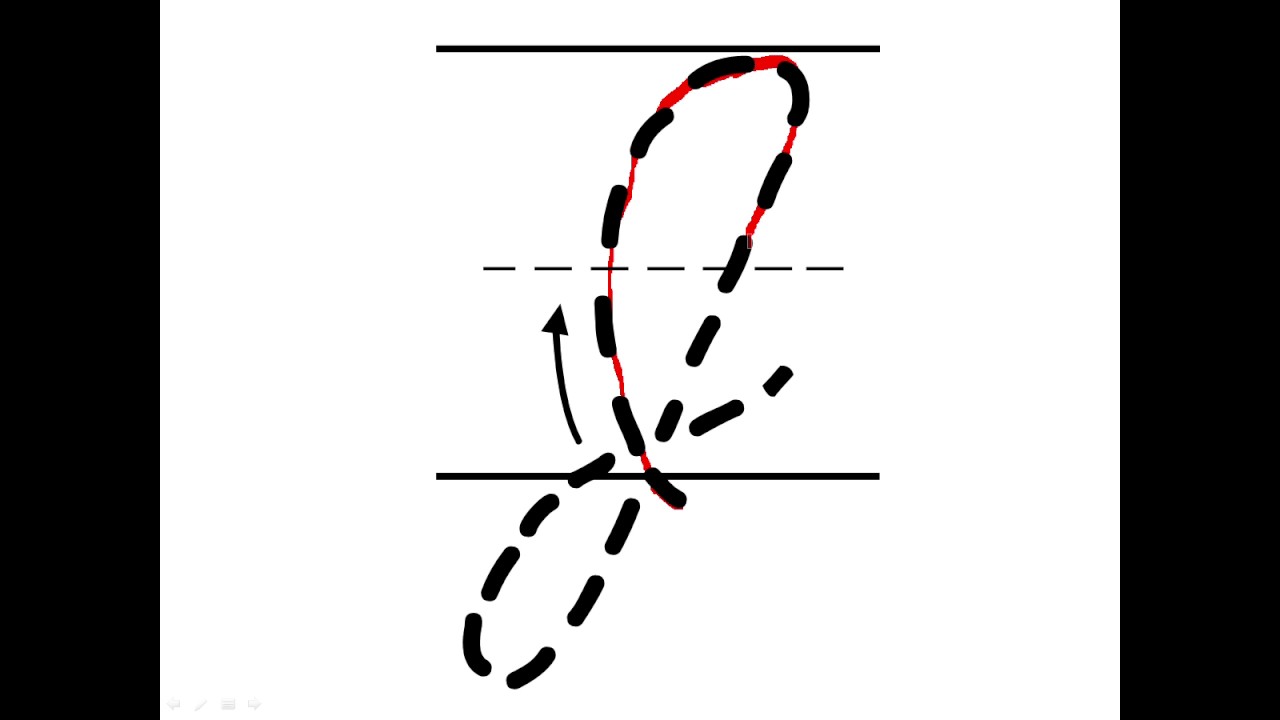

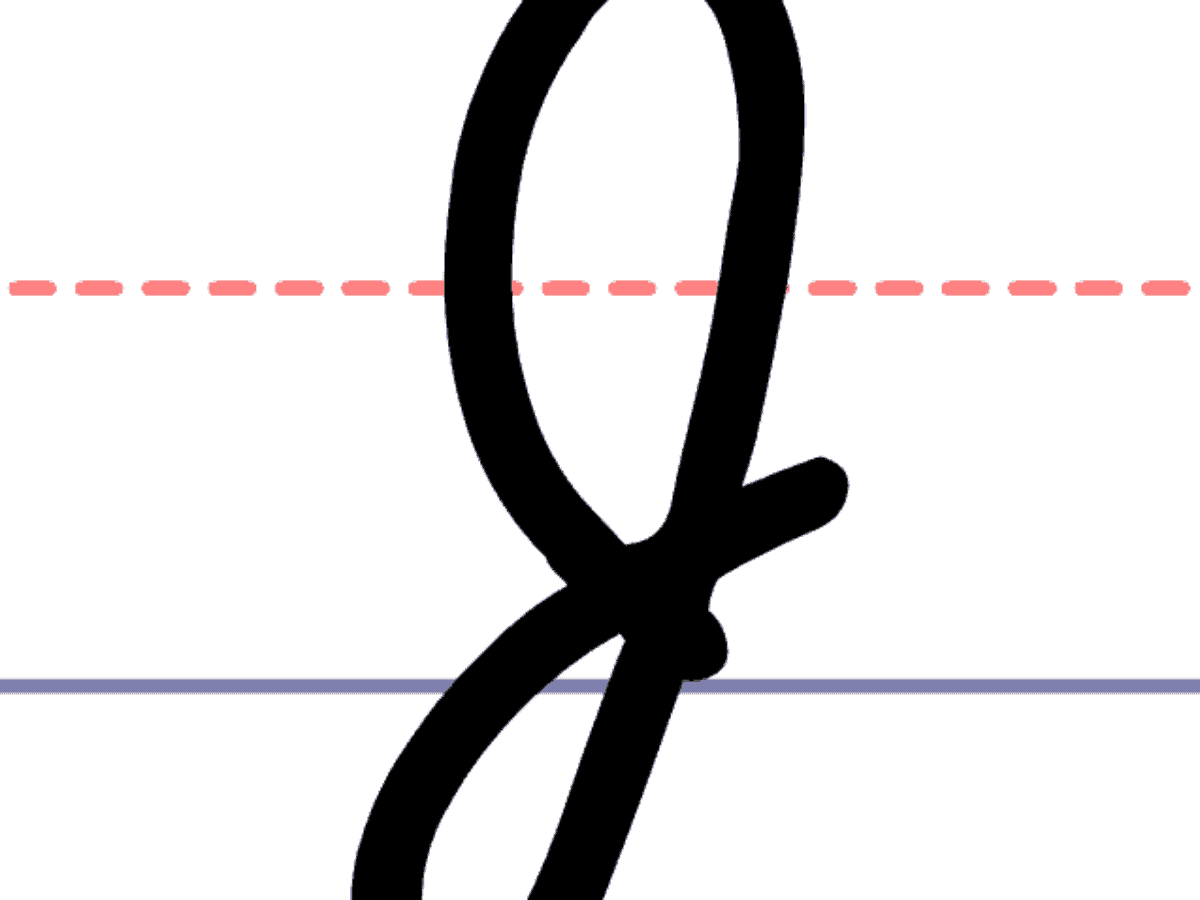

How To Write A Cursive J In Capital – How To Write A Cursive J In Capital

| Welcome in order to my personal blog site, in this moment I will teach you in relation to How To Clean Ruggable. And now, this can be the initial image: