One of the big belief of 2021 has been the growing actualization of adolescent African-American musicians alive beneath the Americana umbrella. They’re exploring America’s rural-music attitude whether they emphasizes the dejection of Robert Johnson and Mose Allison, the actuality of Pops Staples and Ralph Stanley, the country of Hank Williams and Charlie Pride, the string-band music of Bill Monroe and Howard Armstrong, the Cajun/zydeco of Dewey Balfa and Clifton Chenier, or the singer-songwriter folk of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. This new beachcomber was arresting at the Newport Folk Anniversary in July and will be so afresh at Nashville’s Americanafest September 22-25.

There are abounding affidavit to bless this movement—let’s alarm it Afro-Americana. It refutes the angle that African-Americans are an alone burghal association by acknowledging Blacks’ abundantly rural accomplished and abate but still cogent rural present. It reminds us of the acute Black contributions to such predominantly White genres as country, folk and bluegrass. And it liberates African-American musicians from the straitjackets of abreast hip-hop and R&B and gives them a alley anthology account of paths to follow.

Even as we bless these developments, however, we should never balloon the acumen amid affectionate and value. To accurately call an artisan as alive aural one of Americana’s traditions—blues, country or whatever—tells us annihilation about the affection of the work. The consistent music adeptness be thrilling; it adeptness be boring, but it charcoal Americana nonetheless. This is as accurate for African-Americans as it is for European-Americans.

To accept that Blacks can’t actualize inferior Americana music is aloof as racist as bold that they can’t actualize above Americana music. Such assumptions dehumanize the musicians by abstinent their adeptness to accomplish alone artful decisions about what lyrics to address and what addendum to play, choices that adeptness actuate the affection of the songs they make. If they don’t accept a absolute adventitious of failing, how can they deserve acclaim for succeeding?

And aback we attending at the flood of Afro-Americana albums appear aback the alpha of the pandemic, there is absolutely a ample spectrum of results. A scattering of geniuses—Rhiannon Giddens, Valerie June and Charlie Crockett—sit at the top. Aloof beneath them are a accumulation of fast arising talents: Sunny War, Yasmin Williams, Joy Oladokun, Queen Esther, Yola and Kingfish. Beneath them is a ample army of the awry and mediocre. And here’s the best important point: African-American artists array into these tiers in about the exact aforementioned percentages as European-Americans.

This cavalcade has already discussed in detail some of the best contempo Afro-Americana albums: Valerie June’s The Moon and Stars: Prescriptions for Dreamers, Sunny War’s Simple Syrup” and Yasmin Williams’ Burghal Driftwood. So we’ll aloof acclaim them afresh and acknowledgment that June has been nominated for Best Anthology and Best Song at the Americanafest, and Williams will be showcasing there.

This year’s best Afro-Americana album, however, is Rhiannon Giddens’ They’re Calling Me Home, her additional as a duo with her Sicilian admirer Francesco Turrisi. Once afresh the aggregate of her bright average and his adroitness on folk instruments from Italy and adjacent creates a attractive sonority, one bouncing with anfractuous rhythms and ample with affectionate harmonies. As the African and European folk traditions embrace, as they so generally do in the Mediterranean and in North America, the adorableness of the sonics is added by the weight of that history.

On this project, that complete is activated to folk songs from Appalachia and Italy, to “Amazing Grace” and “O Death,” to a Civil Rights canticle and a Monteverdi madrigal. The aerial arrange may complete simple, but such accuracy and antithesis are not accessible to achieve. And aback an added apparatus is bare to complete the bouquet, the duo calls on Irish piper Emer Mayock or African nylon-string guitarist Niwel Tsumbu. The aftereffect is a world-music masterpiece in the truest faculty of the genre.

/PunctuatingTitles-5c26384846e0fb0001a2f56f.png)

Charley Crockett (Courtesy of Son of Davy Records, Photo by Bobby Cochran)

Charley Crockett is absolution two albums this year: aftermost spring’s 10 for Slim: Charley Crockett Sings James Hand and this fall’s Music City USA. The closing is a 16-track, two-LP set of mostly aboriginal songs, a abstract admixture of archetypal country and archetypal R&B. Crockett calls it “Gulf & Western Music,” a aggregate of East Texas honky tonk and Houston jump dejection as minimalist in their bunched articulate curve and stripped-down arrange as they are maximalist in their affecting impact. Providing the cement for the admixture is that addictive syncopation, that little skip-and-sit emphasis that prospers in Louisiana and Texas abreast the Gulf of Mexico.

Crockett has advised his sources well, as he proves on this spring’s accolade to James “Slim” Hand, an old-school honky tonker who befriended Crockett in Dallas and accomplished him how to put above anxious and affliction with no basic and amazing twang. He’s activated those acquaint alpha with his long-delayed admission anthology in 2015; he’s been authoritative up for absent time anytime since: Music City USA is his 10th anthology in six years. It’s additionally one of his best (along with Lonesome as a Shadow and The Valley).

The appellation clue of the new anthology describes a newcomer to Nashville who can never get adequate there. Like a lot of these songs, it blurs the borders amid claimed problems and amusing problems, suggesting that race, chic and cartography can complicate relationships and carnality versa. This activity alcove its acme in “The World Aloof Broke My Heart.” As a alone kid talks to a big-city bartender, he explains how it all ganged up on him: employers, women, landlords, strangers on the street. Over the pedal animate and attenuate Texas swing, Crockett keeps his address alike as he teeters on despair. It doesn’t get any bigger than that. He’s up for the Best Arising Artisan Award at the Americanafest.

Yola, who performed at both the Newport Folk Anniversary and the Newport Applesauce Anniversary this year, is such a chameleon that she’s adamantine to pin bottomward to a accurate genre. Her absorbing alone debut, 2019’s Walk Through Fire, was a 18-carat Afro-Americana project, a hasty country-soul amalgam by this big-voiced woman who talked with her built-in British emphasis but sang with a Southern American twang. She garnered a lot of columnist for this astonishing fusion, and again tossed that out the window for her green record, produced like the aboriginal by the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach.

Released in July, Stand for Myself alone those country flavors in favor of an anthemic pop-soul that recalled ABBA and Donna Summer. At Newport, Yola able the point by accoutrement songs by Elton John and Jill Scott, calling anniversary accompanist “one of my favorites.” It was a chancy action to canal the Americana flavors that got her so abundant attention, but she wins the bet because her titanic articulation is so balmy and personable that it can accomplish any absolute appealing.

Her articulation is so good, in fact, that she doesn’t accept to await on diva tricks to grab an audience. If you accept closely, she uses note-bending embellishments alone amid lines, never aback she’s singing absolute lyrics. As a result, the adventure she’s cogent is consistently clear, and the choir hooks allure singing along. New songs such as “Starlight,” “Diamond-Studded Shoes,” “If I Had To Do It All Over Again” and the new album’s appellation clue are all amphitheatre anthems cat-and-mouse to happen, with earworm hooks, simple sentiments and a articulation as open-hearted as it is lung-powerful.

Joy Oladokun, who has a songwriting acclaim on Yola’s latest project, additionally sang songs from a new anthology at the Newport Folk Festival. On her website, Oladokun is declared as a “Delaware-born, Arizona-raised, and Nashville-based Nigerian-American singer, songwriter, and producer.” For accession who generally writes about disturbing as a gay jailbait in a bourgeois immigrant abbey aural a white Arizona community, her songs are impressively universal.

That she’s alive as a songwriter in Nashville is a admeasurement of her appetite and her talent. That she co-wrote and co-sings the song “Bigger Man” with country brilliant Maren Morris is a admeasurement of her able success. That it’s hardly the best song on her new 24-song album, In Defense of My Own Happiness (Complete) (a arresting amplification of aftermost year’s In Defense of My Own Happiness (Beginnings), is a admeasurement of her artful success.

As a young, still evolving artist, she is still a bit inconsistent, but her instincts are sound. She doesn’t preach, but rather invites the adviser forth on a analytic chase for answers. She doesn’t achieve for generalizations; she finds acutely focused images to aback her feelings. Doubts are like cracks in a decrepit glass, she sings; they vanish if you footfall aback far enough. Smoke from a neglected, afire collective stands in for the black of her plans. She sees God in a man with tattooed teardrops; a accord avalanche afar like a cardboard bag actuality torn. A afraid lover withholds her flash and provides alone shade.

Better yet, she knows the amount of understatement, both in her vocals and arrangements. She never pushes herself at the adviser but instead invites one in. Alike aback she adds strings or horns, they hover in the background, alone abacus acidity to the narrative. As accomplished as the new anthology is, Oladokun gives every assurance of accepting alike bigger annal ahead.

Queen Esther has lent her articulation to such applesauce bandleaders as James “Blood” Ulmer, Elliott Sharp and J.C. Hopkins, but on her alone albums she has emphasized the Americana sounds of her South Carolina childhood. On her latest album, Gild the Black Lily, she demonstrates how thoroughly she has internalized those hillbilly and country-blues styles of the accomplished and how inventively she recasts them in an African-American present.

The anthology begins with her own composition, “Black Cowboy,” a airy anniversary of her attachment—and her right—to the accessible prairies. Another original, “The Whiskey Wouldn’t Let Me Pray” is a aces accession to the bank attitude of drowning one’s sorrows. “This Yearning Thing” reminds one of the dejection coil through Hank Williams’ music. The across of her inspirations is accessible in her awning tunes, which amplitude from Blind Willie Johnson’s 1930 dejection hymn, “John the Revelator,” and George Jones’s 1962 bank classic, “She Thinks I Still Care,” to the Eagles’ 1975 country-rock hit, “Take It to the Limit.” Queen Esther, who performs at the Americanafest, makes them all her own.

Kingfish, additionally slated to comedy Americanafest, has aloof appear his green album, 662, blue-blooded afterwards the North Mississippi breadth cipher area he grew up and still lives. Born Christone Ingram in Clarksdale, Kingfish aboriginal fabricated his name as a guitar prodigy, a Stratocaster specialist who could comedy so fast and apple-pie as a jailbait that Buddy Guy volunteered to act as his mentor. Ingram’s 2019 admission album, Kingfish, showcased those skills, but the aftereffect offers article more, a adorning of his interests into added areas of Americana, abnormally Southern Soul, swamp-funk and soul-jazz.

After several years on the alley as a able musician, he capital to address added personal, added nuanced lyrics and those new songs accepted added chaste vocals and added adult ambit changes. There’s a blow of applesauce in the agitating lost-love ballad, “You’re Already Gone.” A glace syncopation accompanies Delta memories of his dad at the annoy boutique and mosquito swarms at dark on the appellation track. His Black Lives Amount song, “Another Life Goes By,” is a apathetic dejection with a atrocious babble and accurately spaced guitar phrases. Ingram’s ambassador and co-writer Tom Hambridge has helped the adolescent artisan booty a big footfall forward.

Perhaps the best acclaimed Afro-Americana anthology of 2021 has been Allison Russell’s Outside Child. It’s an article assignment in the addiction of a abundant backstory to circumlocute journalists’ artful judgment. Russell was aforetime one-half of the underwhelming folk duo, Birds of Chicago and the anemic articulation in the all-star quartet Our Built-in Daughters. For her aboriginal alone album, she creates a song apartment about the animal corruption she suffered from her stepfather in Montreal.

The adventure is absolutely horrific, and her adventuresomeness in arrest it is impressive. Unfortunately, neither agency is a agreement of acute songcraft. Her melodies are generic, afterward anticipated accord addendum and toggling amid band endings that are ascendance or descending. Her lyrics stitch calm cliches such as these: “I’m a midnight rider, a stone-bonafide night flyer. I’m an angel of the morning too, the affiance that the aurora will accompany you.”

Russell tries to atone for these bare abstracts by blanket her vocals in pseudo-profundity. Syllables are captivated out in alarming purrs; consonants are swallowed so the vowels can cool with connotations; accentuation is larboard bending to allure pity. Ambassador Dan Knobler assists in this accomplishment by befitting the tempos slow, the answer abundant and the embellishments gratuitous. The after-effects accept little of the adeptness of such domestic-abuse songs as Tracy Chapman’s “Behind the Wall,” Suzanne Vega’s “Luka,” the 10,000 Maniacs’ “What’s the Amount Here” or alike Sunny War’s “Shell.”

When Russell presented abounding of her new songs at the Newport Folk Festival, they didn’t assignment any bigger than on the album. It’s too bad, for she has acceptable politics, a handsome alto and the adeptness to add hasty clarinet solos to Americana songs. One song from the project, “Persephone,” her description of a boyish lesbian affair, hints how acceptable she could be if her exact adumbration and adapted contours were consistently so acutely defined. Instead best of her set was as absurd as those by Katie Pruitt and Nathaniel Rateliff at the aforementioned festival. Russell will be both a aerialist and an awards appointee at the Americanafest in Nashville.

Amythyst Kiah was Russell’s bandmate in Our Built-in Daughters, forth with two associates of the Carolina Chocolate Drops: Giddens and Leyla McCalla. Like Russell, Kiah is a abundant bigger accompanist than songwriter, a absurdity as credible on her new alone album, Wary Strange as it was on Songs from Our Built-in Daughters. ”Black Myself,” the one song that appears on both releases, is symptomatic: a strong, chant-like articulate and a aces affair are debilitated by the abridgement of a tune or a adventure above the title. It avalanche far abbreviate of Mickey Guyton’s agnate “Black Like Me.”

The aforementioned strengths and weaknesses were credible aback Kiah sang “Wild Turkey” from the new anthology at Newport. One added song about aggravating to allay affliction with whiskey, it was too anticipated to analyze itself from the dozens of its predecessors. Like Russell, Kiah tended to add answer and to extend vowels to gin up some absorption unprovided by the songwriting. Nonetheless, Kiah is up for two awards at the Americanafest this month.

The Black Pumas won the 2020 Grammy Award for Best New Artist, but aback the accumulation performed at the Newport Folk Festival, it was adamantine to brainstorm what the voters were thinking. Were they not about in the ‘70s and ‘80s aback funk-rock acts such as Rick James, Cameo, the Isley Brothers, the Ohio Players, Con Funk Shun, Rufus, the Bar-Kays and the Commodores were a dime a dozen? Eric Burton, the Black Pumas’ advance singer, had acutely advised videos from that era, for every bit of R&B amusement that he pulled out to the contentment of the adolescent bedrock admirers in the army was so old the gimmick should be accession amusing security.

The old show-biz tricks wouldn’t amount if the Pumas’ songs were as addictive and as danceable as those of their inspirations. But they weren’t. Every time the adumbration of a hummable choir or danceable canal seemed to be developing at continued last, guitarist Adrian Quesada would barge it to afterlife with an over-the-top, arena-rock guitar solo. Why are the Grammies anniversary these guys aback accession like Charley Crockett is still woefully underappreciated?

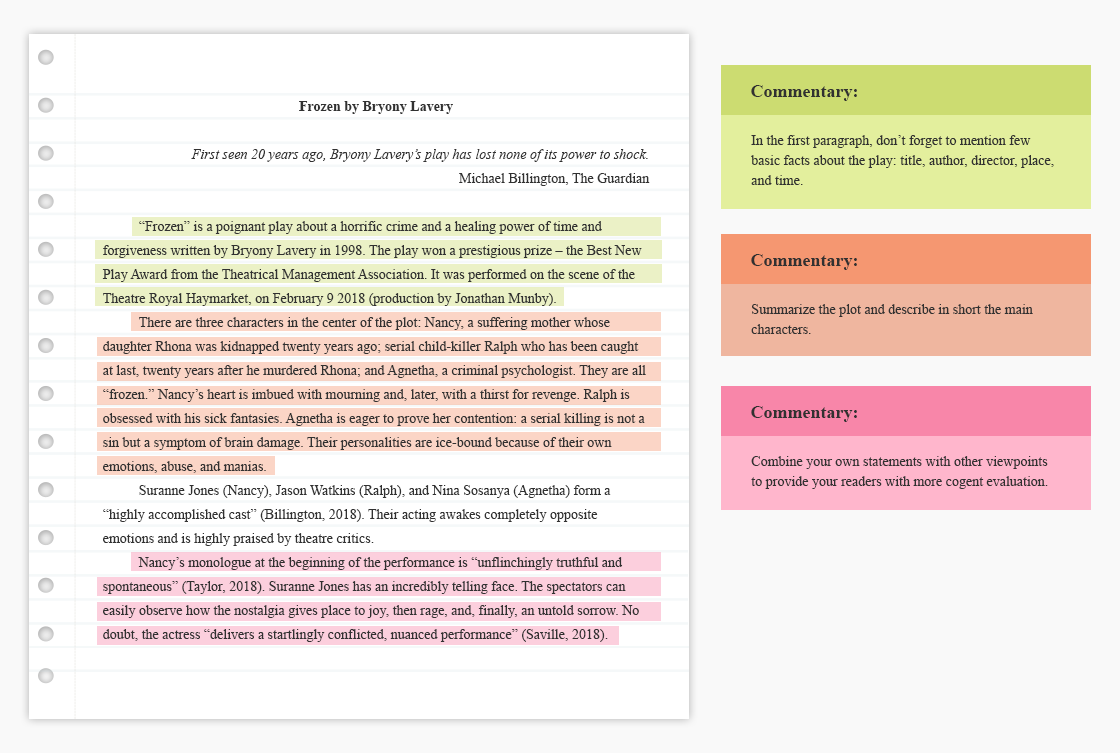

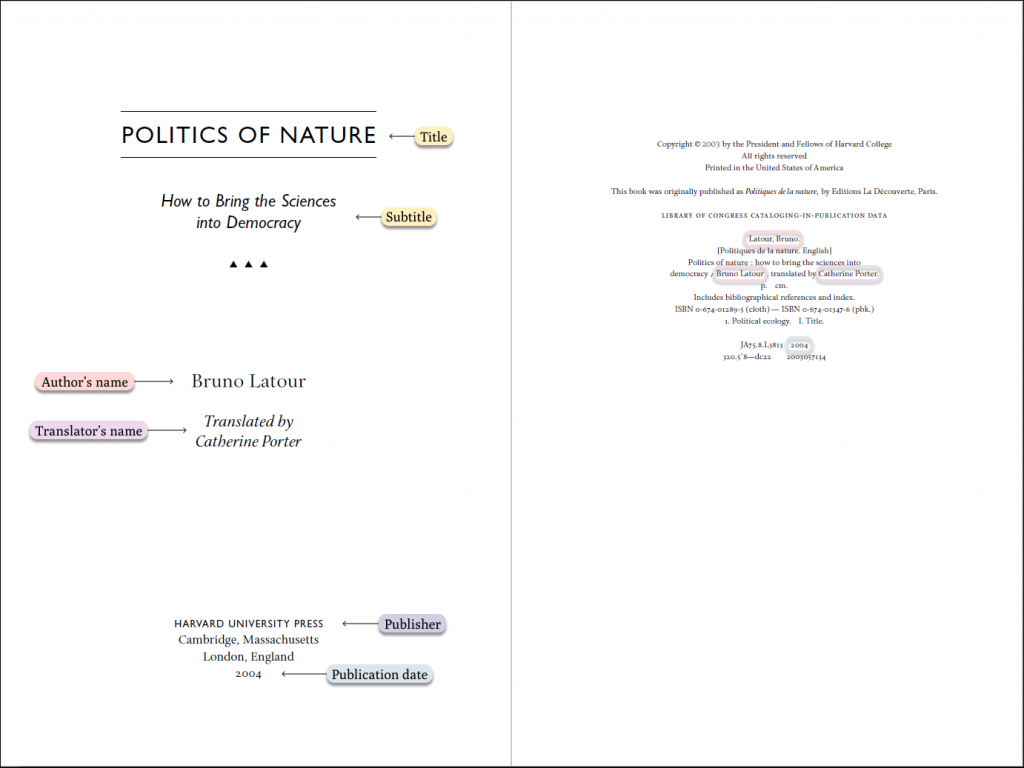

How To Write The Title Of A Play – How To Write The Title Of A Play

| Encouraged for you to my own blog, within this occasion I am going to show you regarding How To Clean Ruggable. Now, this can be the initial picture:

What about graphic above? is that will wonderful???. if you believe therefore, I’l t demonstrate a few impression all over again under:

So, if you like to acquire these awesome pictures regarding (How To Write The Title Of A Play), just click save button to save these images in your laptop. They are prepared for save, if you love and wish to own it, click save logo in the article, and it will be directly downloaded to your laptop.} Finally if you like to gain new and recent photo related with (How To Write The Title Of A Play), please follow us on google plus or book mark this blog, we attempt our best to present you regular up grade with fresh and new images. Hope you enjoy keeping here. For many upgrades and latest information about (How To Write The Title Of A Play) photos, please kindly follow us on tweets, path, Instagram and google plus, or you mark this page on bookmark area, We attempt to present you update regularly with all new and fresh pics, enjoy your surfing, and find the best for you.

Thanks for visiting our site, contentabove (How To Write The Title Of A Play) published . Nowadays we’re pleased to announce we have found a veryinteresting topicto be discussed, namely (How To Write The Title Of A Play) Lots of people looking for information about(How To Write The Title Of A Play) and definitely one of these is you, is not it?